Introduction

지구 온난화로 인한 기온 상승은 양돈 산업에 있어서 중요한 문제가 될 수 있다. 우리나라의 경우, 폭염 주의보(일 최고기온 33℃ 이상) 발생 일수는 매년 증가하고 있으며, 그 강도는 더욱 증가할 전망이다(Park et al., 2016a). 이로 인한, 여름철 평균 기온 상승은 가축의 체온을 증가시키고, 식욕을 감퇴시켜 성장률을 저하시키게 된다(Pearce et al., 2013a; Pearce et al., 2014).

증가하는 여름철 기온으로 인한 높아진 체온을 조절하기 위해 땀샘을 통해 땀을 배출하거나 호흡을 통해 체내의 열을 밖으로 내보낸다. 하지만 돼지는 땀샘의 기능이 약하고 몸의 크기에 비해 폐가 상대적으로 작아 열에 취약하다(Baumgard and Rhoads, 2013; Ross et al., 2015). 또한, 심부의 열을 피부로 이동시켜 체온을 조절해야 하지만, 돼지의 두꺼운 피하지방층이 심부의 열을 피부로 전달하는 것을 방해한다(Ross et al., 2015; Mayorga et al., 2019). 그리고 수컷 돼지는 암컷에 비해 피하지방층이 두껍고 근육과 지방의 비율이 달라 온도에 대한 반응성이 다르다(Armero et al., 1999; Jaturasitha et al., 2008; Muhlisin et al., 2014).

고온 스트레스로 인해 혈액이 심부에서 피부 표면으로 이동하게 되면 장관으로 이동하는 혈류량이 줄어들어 장 세포에 산소 공급이 줄어들게 된다(Pearce et al., 2013b). 이로 인해, 산화적 스트레스와 장 세포 손상이 발생하고 삼투압을 증가시켜 장으로 들어온 독소가 쉽게 체내로 들어오게 된다(Lambert, 2009; Pearce et al., 2012). 뿐만 아니라, 고온 스트레스로 인한 사료 섭취량 감소와 혈류를 통해 장 세포로 공급되는 영양소 공급의 감소는 에너지, 단백질, 그리고 지방 관련 대사 과정과 이와 관련된 대사물질의 변화를 일으킨다(Pearce et al., 2013a; Pearce et al., 2014). 예를 들어, 섭취량 감소로 인한 glucose의 제한된 공급을 보완하고 장 세포를 보호하기 위해 장관 내 glucose transporter의 양을 증가시키거나, 근육 내 단백질의 손상을 일으키고 지방의 축적을 유발한다(Pearce et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2018).

고온 스트레스로 인한 대사 과정의 변화와 이에 따른 생산성 감소를 관리하기 위해 혈액이나 타액에서의 대사물질의 변화에 대한 연구가 진행되었다(Escribano et al., 2013; Dou et al., 2017). 또한, 가축에서 고온 스트레스로 발생하는 아미노산의 이화작용과 혈액 내 아미노산의 변화에 대한 연구가 진행되었으며(Morales et al., 2016a; Guo et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2018), 이러한 대사물질의 변화를 통해 돼지를 고온 스트레스로부터 관리하기 위한 생체 지표 개발이 가능할 것으로 보인다. 따라서, 고온 스트레스와 혈액 내 유리아미노산의 변화에 대한 상관성을 구명하고, 증가하는 여름철 폭염 일수 따른 양돈 관리를 위한 잠재적인 생체 지표를 제시하고자 본 연구를 진행하였다.

Materials and Methods

본 실험은 국립축산과학원 동물사육시설에서 실시되었으며, 동물실험윤리위원회(IACUC) 운영 규정을 준수하고 승인을 받았다(No. 2017-245).

공시 동물 및 시험구 배치

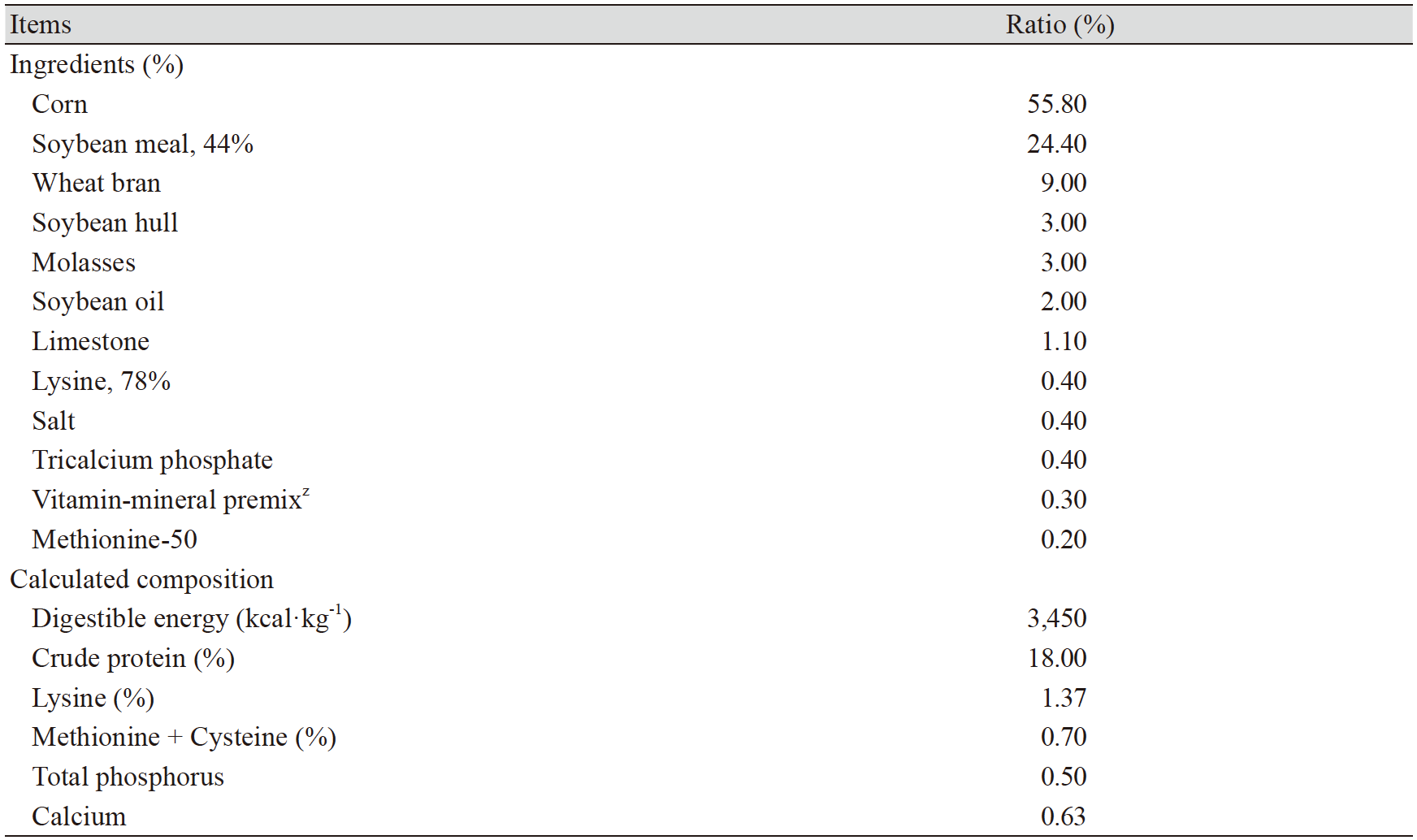

시험 동물은 체중 56.1 kg 전후 듀록종 암, 수 각각 3마리를 공시하였다. 시험 동물은 항온·항습이 유지되는 챔버에서 대사틀에 5일간 사육 온도 25℃, 상대습도 60%의 조건(thermal neutral, TN)으로 적응기간을 두었다. 적응 기간 이후 사육 온도 33℃, 상대습도 60%의 조건(heat stress at 33℃, HS33)으로 24시간 후 혈액을 채취하였다. 시험기간 동안 급여 사료는 옥수수·대두박 위주로 한국돼지사양표준(NIAS, 2017) 영양소 요구량 이상 배합한 사료를 1일 2회로 2 kg씩 급여하였고, 물은 자유 채식하였다. 시험 사료의 원료 구성과 화학적 조성은 Table 1과 같다.

조사 항목 및 조사 방법

돼지의 일당 사료 섭취량, 일일 음수량, 물 허실량을 조사하였고, 혈액 시료는 10:00에 경정맥에서 채취하여 헤파린 처리 후 1시간 이내에 원심분리기로 4℃에서 15분간 원심분리(1,660 × g) 후 상층액을 액체 질소로 급속 동결하여 분석 전까지 - 80℃에서 냉동 보관하였다.

일당 사료 섭취량(average daily feed intake, ADFI)은 전체 사료섭취량에서 시료채취시점에 남은 사료 량을 제외하여 계산하였다. 일일 음수량은 유량계(Daesung, Seoul, Korea)를 니플에 설치하여 매일 투입량을 측정하였고, 워터컵에서 배출되는 물의 양을 회수하여 측정하여 계산하였다.

혈장에서 tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α 분석은 ELISA 분석 kit (R&D system, Minneapolis, USA)를 이용하여 분석하였다. 그리고 nitrate (μmol·L-1)와 total nitric oxide (μmol·L-1) 분석은 parameter 분석 kit (R&D systems, Minneapolis, USA)를 이용하여 분석하였다. 혈장에서 유리아미노산 분석은 이전 연구에서 제시된 방법으로 전처리 하였다(Reverter et al., 1997). 그 후, 아미노산 전용 분석기(Hitachi L8900, Tokyo, Japan)를 이용하여 혈장 내 유리아미노산을 정량 분석하였다.

통계 분석

통계 처리는 돼지의 사육환경 조건에 의한 사료 섭취량, 음수량, 혈장 아미노산 등의 함량은 SAS프로그램(SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC, USA)의 GLM procedures를 이용하여 진행하였으며, 사육환경 조건에 따른 평균 간의 유의성 검정은 Duncan검정에 의해 95% 유의수준으로 분석하였다.

Results and Discussion

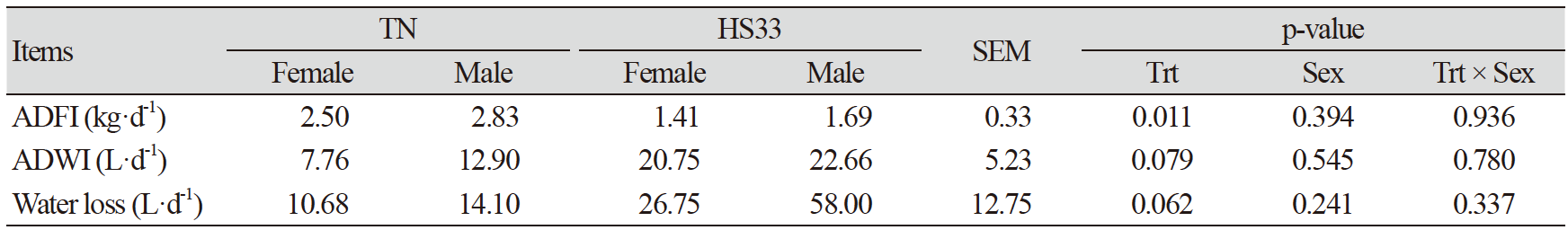

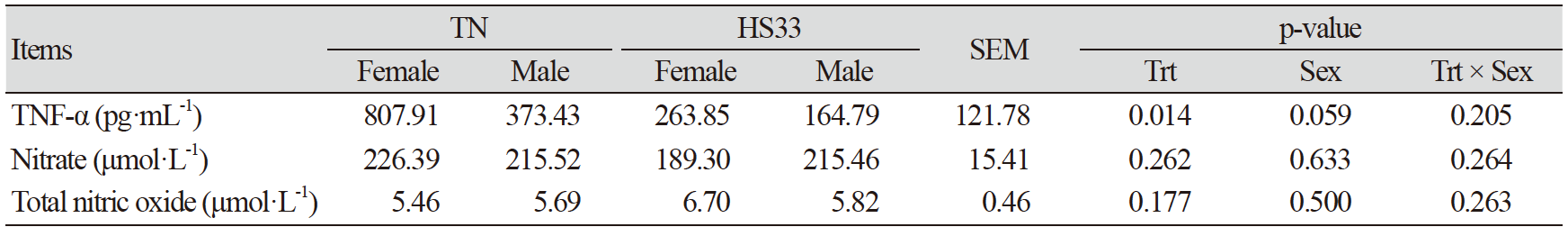

돼지가 고온 스트레스를 받지 않고 정상적인 몸 상태를 유지하기 위해서는 열적 중성(thermal neutral, TN) 온도가 필요하며, 이 온도의 구간은 열적 중성권(TN zone)이다. 일반적으로, 상대적으로 체중이 많이 나가는 육성·비육돈의 TN zone이 이유자돈보다 낮고, 고온에 대한 반응성 또한 이유자돈에 비해 육성·비육돈이 더 크다(Cottrell et al., 2015). 본 연구에서 사용된 육성돈의 TN온도는 25℃이하이다(Quiniou et al., 2001). 하지만, HS33 처리구에서 사료섭취량이 TN보다 유의적으로(p<0.05; Table 2) 감소하였고, 음수량과 물 허실량이 증가하는 경향(p<0.10; Table 2)으로 보아 돼지들은 고온 스트레스를 받은 것으로 보인다. 사료섭취량이 감소한 이유는 고온 스트레스로부터 몸을 보호하기 위해 체내 대사열 생산을 최소화하기 위한 것으로 보이며, 이전 연구에 의하면 고온 스트레스처리 후 24시간 동안 사료효율 감소로 인한 체내 이화작용과 탈수증상을 일으킨 것으로 보고되었다(Pearce et al., 2013a; Park et al., 2016b; Lu et al., 2018). 뿐만 아니라, 고온 스트레스를 받은 돼지들은 몸을 보호하기 위해 친염증성 사이토카인인 TNF-α의 발현량을 조절한 것으로 보인다. HS33은 TNF-α를 TN과 비교하여 유의적(p<0.05; Table 3)으로 감소시켰으며, 이는 TNF-α로 인해 발생하는 apoptosis로부터 몸을 보호하기 위한 방어기작으로 보인다(Qu and Ajuwon, 2018). 하지만, 수컷의 TNF-α 수치가 암컷에 비해 낮은 경향(p<0.10; Table 3)으로 보아 고온 스트레스로부터 몸을 보호하기위한 수컷의 방어기작이 암컷보다 더 강했을 것으로 보인다. 또한, 암컷보다 상대적으로 두꺼운 수컷의 피하지방층과 암컷의 성호르몬에 의한 영향이 성별에 의한 결과의 차이를 보여준 것으로 판단된다(Armero et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2007).

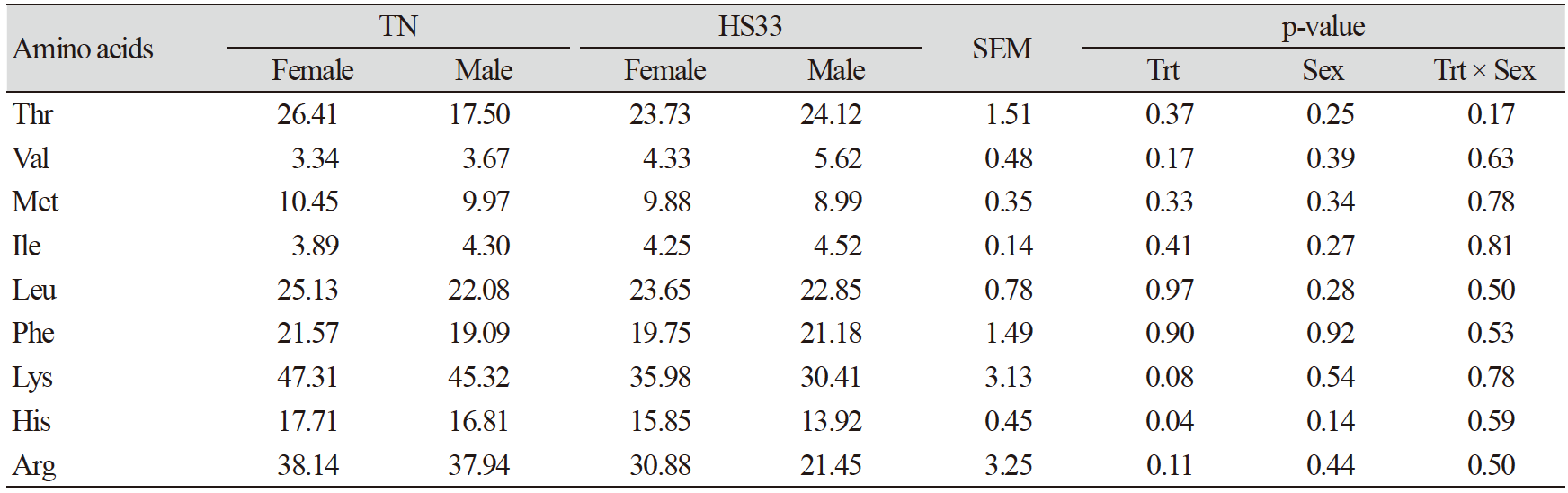

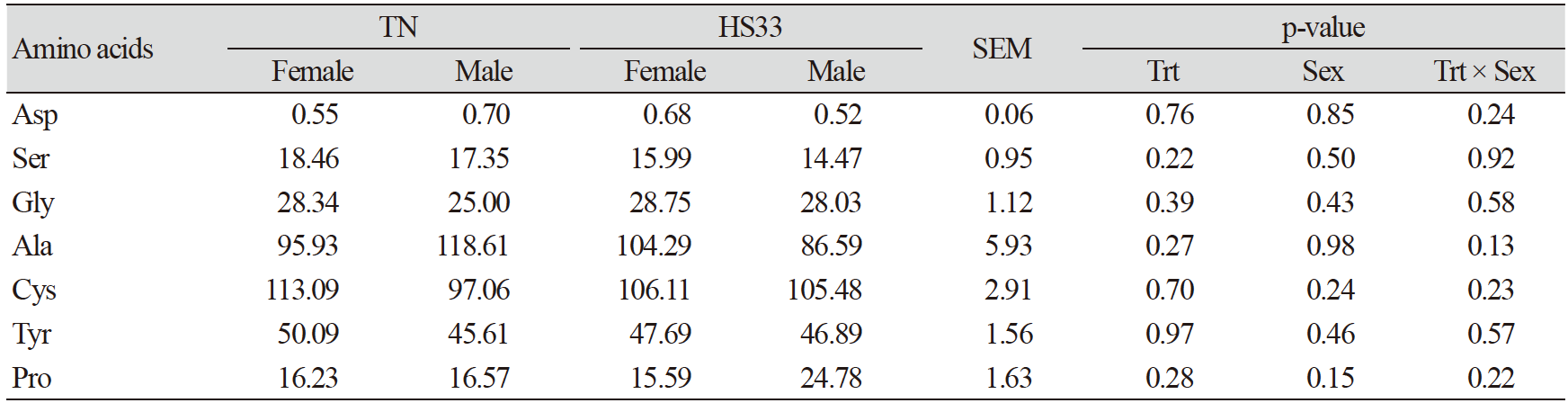

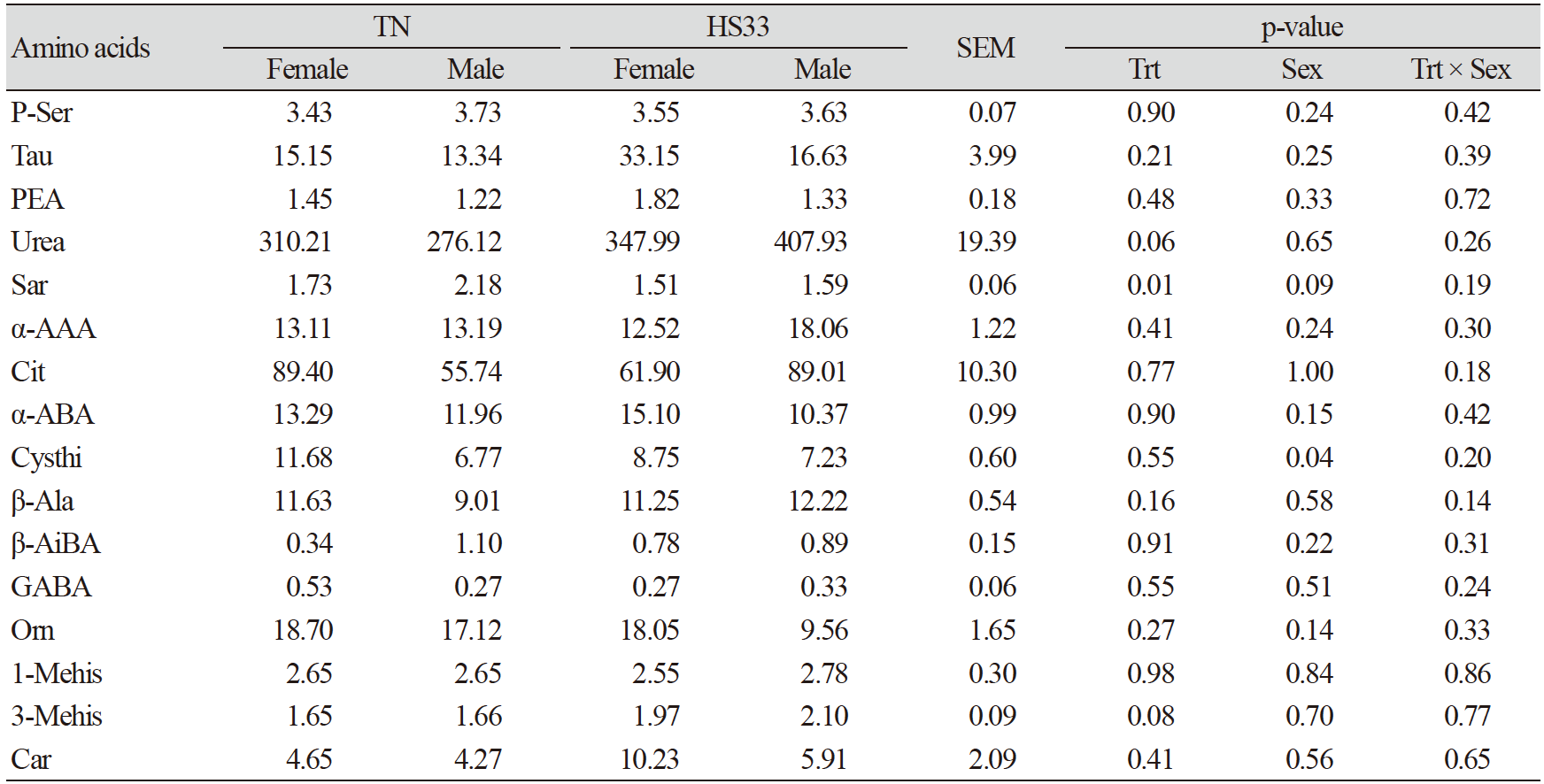

고온 스트레스는 혈장 내 필수 아미노산인 histidine (His)과 비단백질 아미노산인 sarcosine (Sar)의 결과에 영향을 주었고, 이것은 고온 스트레스에 의한 산화적 스트레스로부터 몸을 보호하기 위한 작용때문이다. 하지만, 혈장 내 비필수 아미노산의 함량은 변화가 없었다(Table 5). His은 장 염증을 완화시켜주는 물질이며, 항산화 기능을 가진 carnosine (Car)합성의 전구체이고, His과 Sar은 고온 스트레스에 의해 발생하는 활성산소를 줄여준다(Boldyrev et al., 2013; Akbarian et al., 2016; Morales et al., 2016b). 본 실험에서 HS33 처리구의 His과 Sar은 TN에 비해 유의적(p<0.05)으로 감소하였다(Table 4 and Table 6). 따라서, 고온 스트레스를 받은 돼지들의 혈장에서 항산화 기능을 가진 두 아미노산(His과 Sar)의 감소는 항산화 스트레스를 유발하는 물질들을 줄이기 위해 사용되었을 것이다(Morales et al., 2016a). 하지만, 이전 연구결과에 의하면 만성 고온 스트레스를 받은 육성돈의 혈청 내 Car과 Sar 모두 감소하였지만, 본 실험에서 급성 고온 스트레스를 받은 육성돈의 혈장 내 Car의 양은 유의적인 차이가 없었다(Table 6; Morales et al., 2016a). 이는 각 실험에서 사용된 고온 스트레스 조건(만성 vs. 급성)의 차이 때문으로 판단된다(Morales et al., 2016a).

고온 스트레스는 육성돈의 근육 내 단백질의 손상과 이화작용을 일으켰을 것이며, 이는 혈액 내 urea와 3-methylhistidine (3-Mehis)의 변화와 연관이 있다. 본 실험에서 HS33처리에 의해 urea와 3-Mehis 모두 TN보다 증가하는 경향(p<0.10; Table 6)을 보였으며, 이러한 결과는 고온 스트레스에 의해 근육의 손상과 분해가 일어난 것을 암시한다(Pearce et al., 2013a; Morales et al., 2016a). 하지만, 유의적인 차이가 없었기 때문에 본 실험에서 사용된 급성 고온 스트레스는 육성돈의 근육 내 단백질에 미친 영향이 크진 않았음을 의미한다.

Conclusion

본 연구는 급성 고온 스트레스 처리에 따른 육성돈의 사료 섭취량, TNF-α, 그리고 혈장 내 아미노산의 비교를 통하여 고온 스트레스가 돼지에게 미치는 영향을 평가하였다. 고온 스트레스는 사료섭취량과 TNF-α를 감소시켰으며, histidine과 sarcosine의 농도를 감소시켰다. 사료섭취량과 TNF-α의 감소는 사료 섭취에 의한 대사열을 감소시키기 위함이고, TNF-α에 의해 발생하는 apoptosis로부터 몸을 보호하기 위한 방어기작으로 판단된다. 또한, histidine과 sarcosine의 감소는 고온 스트레스로 인해 발생하는 산화적 스트레스를 줄이기 위해 이용되었기 때문에 줄어든 것으로 판단된다. 따라서, 본 연구 결과에서 고온 스트레스에 의해 변화하는 아미노산들은 고온 스트레스 지표로써 가능성을 보여준다.

Authors Informaion

Byeonghyeon Kim, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4651-6857

Minji Kim, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2106-1921

Hye Ran Kim, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2207-3668

Sang Yun Ji, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7235-3655

Ki Hyun Kim, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9834-2126

Ju Lan Chun, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4618-586X

Youl-Chang Baek, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4454-5339

Yookyung Lee, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9896-4152

Jin Young Jeong, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8670-7036

Sung Dae Lee, Rural https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9167-4099