Introduction

The use of chemical pesticides is an integral part of modern agricultural methods to improve plant yields. However, their extensive use and misuse could lead to the persistent retention of pesticides in the soil for many years, causing soil and water pollution. Among various commonly used pesticides, fipronil is a major broad-spectrum pesticide used in agriculture worldwide (Pandya et al., 2018; Shakya et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2021). However, due to overuse and mishandling, the impact of fipronil and its main metabolites on different living organisms have gained the attention of researchers over the past few years. Dermal contact or ingestion of fipronil by insects inhibits the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-gated chloride channel (Gant et al., 1998). Once introduced into the environment, fipronil undergoes several chemical reactions, such as reduction, oxidation, hydrolysis, or photolysis. These reactions convert fipronil into its main metabolites viz. fipronil sulfone, fipronil sulfide, fipronil desulfinyl, and fipronil amide (Weston and Lydy, 2014; Qu et al., 2016) which can persist in contaminated water, soil, food, or within bodies of animal (Hainzl et al., 1998; Gunasekara et al., 2007).

In vertebrates, fipronil sulfone (FS) the main metabolite of fipronil, is believed to play a significant role in fipronil-associated poisoning. Exposure to FS has been reported to cause headaches, dizziness, sweating, nausea, vomiting, agitation, and seizures in animals (Mohamed et al., 2004). Compared to the parent compound, FS is believed to be more toxic due to its higher binding affinity for GABA receptors (Cravedi et al., 2013). A review of past studies reveals that fipronil has the potential to negatively affect reproductive function in mammals. Fipronil and its metabolites have been found to impair the development and quality of embryos in females (Yan et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2017; Šefčíková et al., 2018) and cause abnormalities in sperm function and spermatogenesis in males (De Barros et al., 2017; Bae and Kwon, 2020). FS has a relatively long half-life in vertebrates compared to fipronil and remains in the body for a long time. In an earlier study, we reported the effects of direct exposure to fipronil on boar spermatozoa which resulted in an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and impaired fertilizing capacity (Adikari et al., 2022). Therefore, in this study, by examining the effect of FS, a metabolite of fipronil, the direct effect of metabolites of pesticides remaining in the body on germ cells was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Sperm preparation

Liquid boar semen with more than 80% sperm motility was procured from a local artificial insemination (AI) center and used for the experiments. Fipronil sulfone (PESTANAL®, Cat. No. 32333, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to the required concentration. Boar spermatozoa were washed and resuspended in Beltsville thawing solution (BTS; Pursel and Johnson, 1976), followed by incubation a) without FS (or with DMSO [solvent]; controls) and b) with 10 - 200 µM FS, at 37℃ for 30 min and 2 hrs. Unless otherwise mentioned, all other reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., LLC (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Evaluation of sperm motility

A computer-assisted sperm analysis system (Sperm Class Analyzer®, Microptic, Barcelona, Spain) was used to evaluate sperm motility. The method, in brief, was as follows: Spermatozoa were incubated for 30 min at 37.5℃, after which 2 μL aliquot of the semen sample was placed on a pre-warmed (38℃) Leja counting slide (Leja products B.V., Nieuw-Vennep, The Netherlands), and 10 fields were examined at 37.5℃, assessing a minimum of 500 spermatozoa per sample. The proportion of total motile spermatozoa (%), hyperactive spermatozoa (%), and progressive motile spermatozoa (%) was then determined. The following kinetic parameters were measured in the treatment samples: curvilinear velocity (VCL, µm·s-1), straight-line velocity (VSL, µm·s-1), average path velocity (VAP, µm·s-1), percentage of linearity (LIN, %), percentage of straightness (STR, %), and wobble percentage (WOB, %).

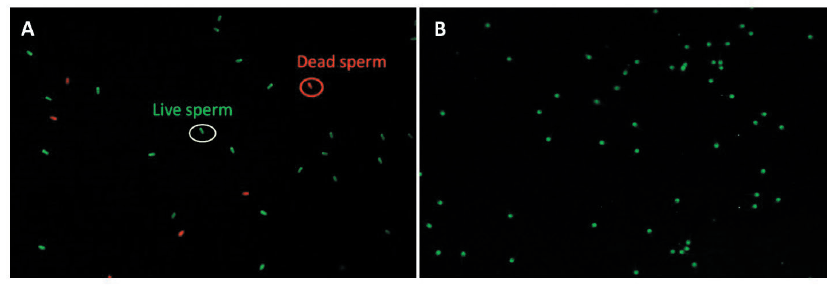

Measurement of sperm viability

Incubated spermatozoa (1 × 108 cells·mL-1) were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% (w·v-1) polyvinyl alcohol (PBS-PVA). Following the manufacturer’s protocol, sperm viability was assayed using the LIVE/DEAD® Sperm Viability kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), which contained the DNA dyes SYBR14 (final concentration: 100 nM) and propidium iodide (PI; final concentration 1 μM). The stained slide images of the spermatozoa were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ci microscope, Nikon Instruments Inc., Seoul, Korea) with a camera (DS-Fi2, Nikon) and imaging software (version 4.30, Nikon). The spermatozoa were classified and counted as viable (SYBR14) or dead (PI) spermatozoa (Fig. 1A).

Assessment of acrosome integrity

Boar spermatozoa were fixed in 95% ethanol and were then incubated for 30 min at 4℃. After fixation, the sperm were dried onto slides and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled Pisum sativum agglutinin (FITC-PSA; 5 μg·mL-1) for 10 min (Berger, 1990). The acrosome integrity was determined using a fluorescence microscope and imaging software (Nikon). The images of the stained samples were classified into two groups: sperm heads displaying green fluorescence were considered to have an intact acrosome while partial green fluorescence or its absence in the head was indicative of spermatozoa with damaged acrosome and loss of acrosome integrity (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Fluorescence microscopic images of sperm viability (A) and acrosomal integrity (B). A green color circle represents live spermatozoa, while a red color circle represents dead sperm (A). Sperm heads displaying green fluorescence were considered to have an intact acrosome, while partial green fluorescence or its absence in the head was indicative of spermatozoa with damaged acrosome with loss of acrosome integrity (B).

Measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Spermatozoa were washed twice with 0.1% PBS-PVA, and incubated with 1 µM 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2’,7’-dichlorodihydro-fluorescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) at 37oC for 10 min. Thereafter, they were washed twice with 0.1% PBS-PVA, and the stained spermatozoa were observed under a fluorescence microscope equipped with imaging software (Nikon), which measured the fluorescence intensity for ROS production in the spermatozoa.

Real-time PCR analysis

After incubation with or without FS for 30 min, the sperm were washed three times with PBS-PVA. The total RNA was prepared according to the guidelines of the PureLink™ RNA Mini Kit with slight modifications. The RNA concentrations were measured using a nanodrop spectrophotometer (DeNovix Ds-11FX, Wilmington, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from purified RNA using the TOYOBO ReverTra Ace qPCR RT kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in triplicate with the SYBR™ Premix Ex Taq™ II (Bioneer Corp., Daejeon, Korea) using the MyGo Pro PCR cycler (Diagnostic Technology, Belrose, Australia). Relative expression levels of mRNA from the target genes were compared with that of the endogenous control glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The sequences of the specific primers (Table 1) used to measure the relative expression of outer dense fiber of sperm tails proteins 2 (ODF2), zona pellucida binding protein 2 (ZPBP2), heat-shock protein A8 (HSPA8), and A-kinase anchor protein 4 (AKAP4) were created using the Primer Blast software from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard error of means (SEM) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA on the GraphPad PRISM® (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A completely randomized design was applied, and Tukey’s multiple comparison test or t-test was performed to compare the values of the individual treatments. The results were considered statistically significant at p-values, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Results and Discussion

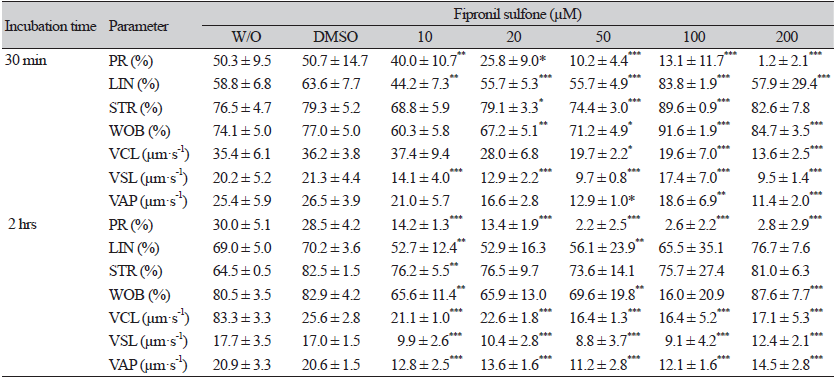

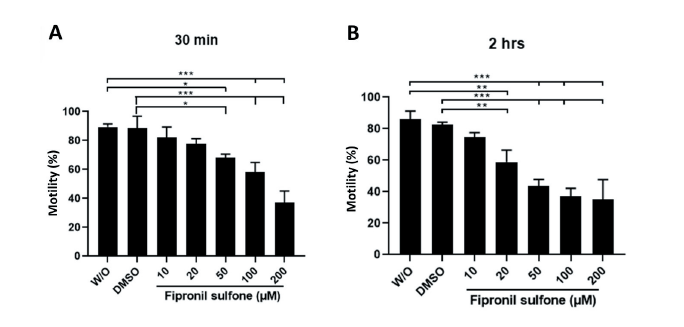

Boar spermatozoa were incubated in the presence of 10 - 200 µM FS and without FS for two time periods, 30 min and 2 hrs, and thereafter, the motility and motion kinetic parameters of spermatozoa were evaluated (Fig. 2; Table 2). For both incubation times, spermatozoa exposed to FS showed a dose-dependent decrement in motility (Fig. 2A and B). When compared to the controls after incubation for 30 min, a significant reduction in sperm motility was observed at 50 - 200 µM FS (88.5 - 89.4% controls vs. 68.2 - 37.1% FS [50 - 200 µM], p < 0.05 and p < 0.001; Fig. 2A). A similar reduction in motility was observed in the spermatozoa exposed to FS for 2 hrs of incubation (82.6 - 86.1% controls vs. 58.7 - 35.0% FS [20 - 200 µM], p < 0.01 and p < 0.001; Fig. 2B). As shown in Table 2, the percentages of sperm progressive motility (PR), straightness index (STR), curve speed (VCL), linear speed (VSL), and average path velocity (VAP) decreased in spermatozoa incubated with FS compared to the controls for both incubation times (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001; Table 2).

Fig. 2. Evaluation of sperm motility. Boar spermatozoa were exposed to varying concentrations of fipronil sulfone (or controls; without [W/O] fipronil sulfone and DMSO) at two different incubation times of 30 min (A) and 2 hrs (B). Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

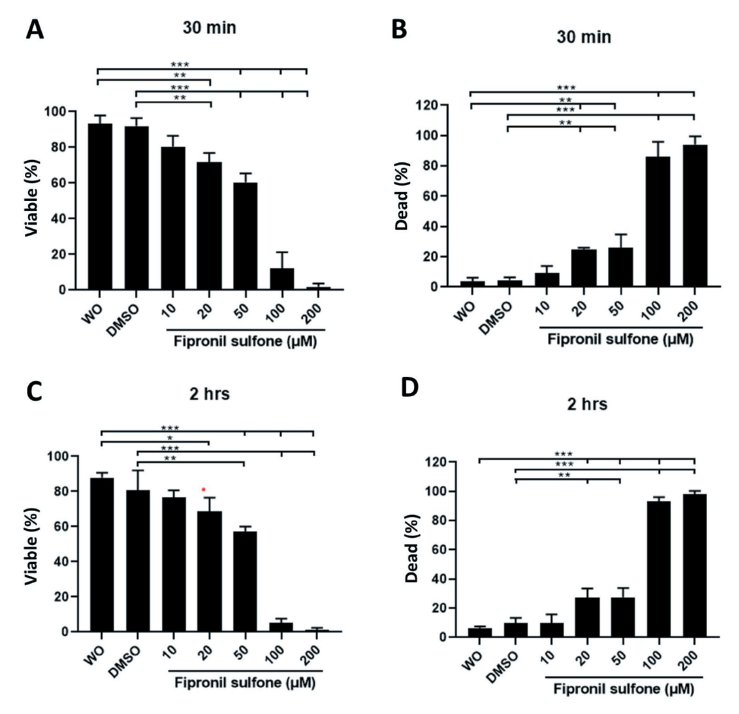

Sperm were stained with SYBR14 and propidium iodide (PI) to evaluate viability, and images were taken under the fluorescence microscope (Fig. 1A and 3). Significantly lower viable sperm percentages were observed in sperm exposed to 100 - 200 µM FS (15.0 - 1.9%) compared to unexposed sperm (without exposure [W/O]: 93.2%, p < 0.01 and p < 0.001; Fig. 3A). FS-treated groups at doses of 20 - 200 µM showed significantly higher percentages of dead spermatozoa (3.7 - 4.6% controls vs. 25.1 - 94.2% FS [20 - 200 µM], p < 0.01 and p < 0.001; Fig. 3B). After 2 hrs of incubation, dose-dependent reductions of viable sperm were observed in the FS-treated groups (80.7 - 87.9% controls vs. 68.8 - 1.3% FS [20 - 200 µM], p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001; Fig. 3C). Similarly, higher dead sperm were observed for the FS concentrations from 20 - 200 µM (6.6 - 9.9% controls vs. 27.1 - 98.0% FS [20 - 200 µM], p < 0.01 and p < 0.001; Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Sperm viability was examined after treatment with different concentrations of fipronil sulfone (or controls; without [W/O] fipronil sulfone and DMSO) and incubation times 30 min (A and B) and 2 hrs (C and D). Spermatozoa that exhibited green fluorescence were considered viable (A and C), while sperm appearing in red color were considered dead (B and D). Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p <0.001. DMSO, dimtehyl sulfoxide.

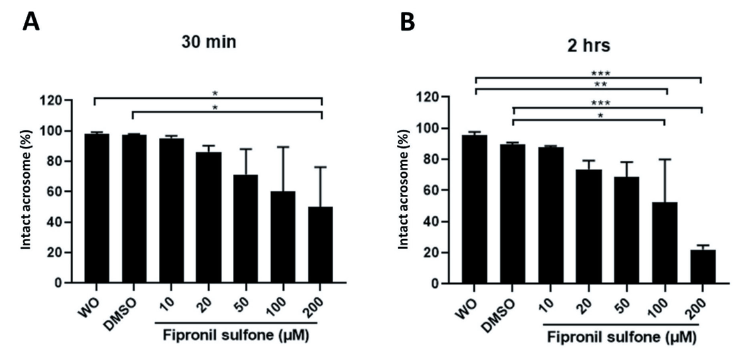

Assessment of acrosome integrity was done by FITC-PSA staining (Fig. 1B and 4). As expected, the lowest intact acrosome percentage after 30 min of incubation was observed in sperm exposed to 200 µM FS (97.3 - 98.1% controls vs. 49.8% FS [200 µM p < 0.05; Fig. 4A), while more decrement was observed in sperm incubated with 100 - 200 µM FS for 2 hrs (89.7 - 95.6% controls vs. 52.4 - 22.1% FS [100 - 200 µM], p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001; Fig. 4B).

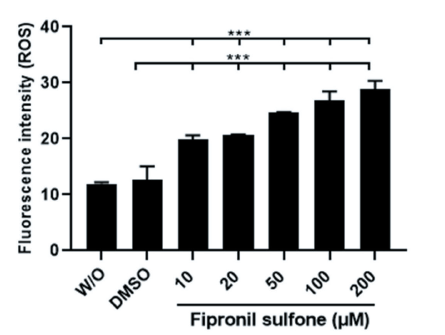

To observe the intracellular ROS production, spermatozoa incubated in the absence or presence of FS for 2 hrs were stained with carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA) solution at 37℃ for 10 min, and the fluorescence intensity was measured in stained samples under the fluorescence microscope. As presented in Fig. 5, higher fluorescence intensities were obtained in sperm treated with 10 - 200 μM FS compared to the control groups (fluorescence intensity [no unit] 11.9 - 12.7 controls vs. 19.9 - 28.8 FS [10 - 200 µM], p < 0.001; Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Acrosome integrity was evaluated in spermatozoa exposed to varying concentrations of fipronil sulfone (or controls; without [W/O] fipronil sulfone and DMSO) and different incubation times of 30 min (A) and 2 hrs (B). Spermatozoa with intact acrosome emit green fluorescence, whereas spermatozoa emitting partial green fluorescence or in which the fluorescence is absent were considered spermatozoa with damaged acrosome with loss of acrosome integrity. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *p <0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. DMSO, dimtehyl sulfoxide.

Fig. 5. Production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in spermatozoa exposed to varying concentrations of fipronil sulfone (or controls; without [W/O] fipronil sulfone and DMSO) after incubation for 2 hrs. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). ***p < 0.001. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

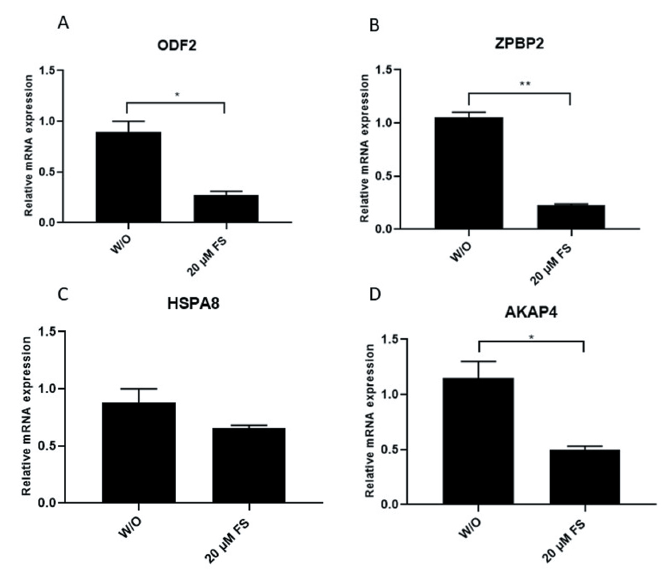

Relative mRNA expressions of ODF2, ZPBP2, HSPA8, and AKAP4 associated with the fertilizing capacity of spermatozoa were examined in sperm incubated with 20 μM FS (Fig. 6). All genes were down-regulated significantly in sperm exposed to FS compared to the controls (W/O FS) (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01; Fig. 6A - D), except for the HSAP8, but it is a lower level than the control sperm without significant difference between groups (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Relative mRNA expression of outer dense fiber 2 (ODF2), zona pellucida binding protein 2 (ZPBP2), heat-shock protein A8 (HSPA8), and A-kinase anchor protein 4 (AKAP4) by real-time (RT) PCR in spermatozoa exposed to 20 μM of fipronil sulfone (control: without [W/O] fipronil sulfone). Relative expression levels of mRNA from the target genes were compared with that of the endogenous control glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. FS, fipronil sulfone.

Since fipronil is a widely used pesticide in the world, the contamination it causes is also considered to be high. Several studies have found that FS, the main metabolite of fipronil, is not eliminated immediately and has a greater potential to remain within the body compared to fipronil. In an experiment, fipronil was orally administered to prairie dogs and rats, and the accumulation levels of both fipronil and FS were measured. It was found that the average FS concentration was approximately 3.2-fold higher than that of fipronil in the prairie dog sera (1.15 vs. 0.36 μg·mL-1) and rat sera (1.77 vs. 0.53 μg·mL-1) (Adikari et al., 2022). In another study involving chicken eggs, the oral and dermal administration of fipronil resulted in the accumulation of FS in the eggs and internal organs (Corrias et al., 2021). These studies indicate that FS has the potential to accumulate in and cause damage to living cells. In the male reproductive system, triiodothyronine (T3) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secreted by the pituitary play an essential role in the maturation of the testis (Kula, 2013). Spermatogenesis consists of miosis and meiosis of spermatogonia, followed by maturation. Any agent that disrupts the steps involved in spermatogenesis will cause the formation of defective spermatozoa (Wagner et al., 2008). Thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) located in the testis are activated by the thyroid hormone which affects the growth and development of the testis (Cooke, 1991; Wagner et al., 2008). However, FS can disturb thyroid function through thyroid receptor catabolism, human cytochrome P450 (CYP), and conjugation enzyme expressions and activities (Cooke, 1991; Roques et al., 2012). Thyroid function and oxidative stress are also linked and oxidative stress can affect the fertility status of mammals (Venditti and Meo, 2006; Sakamoto et al., 2008). In addition, ROS is required for the normal function of all cells including the sperm, but excessive production of ROS is detrimental to sperm as it damages the sperm DNA (Agarwal et al., 2008; Sakamoto et al., 2008). Moreover, oxidative stress and high calcium ion levels can cause the extrusion of cytochrome c and activate the caspase cascade, resulting in apoptosis and lipid peroxidation (Amaral et al., 2013). From the results of the present study, we observed that sperm exposed to FS had a higher ROS production compared to the controls (Fig. 4). FS has the potential to block the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors (Zhao et al., 2005; Li and Akk, 2008) which are important for regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and any impairment of this system will adversely influence mammalian reproduction (Watanabe et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2014). Furthermore, in the present study, we observed a reduction in motility, viability, and normal acrosome percentages in sperm exposed to FS (Fig. 1 - 3).

Conclusion

Direct exposure to FS, a metabolite of fipronil significantly reduces the motility, viability, and acrosomal integrity of boar spermatozoa. Intracellular ROS production increased in spermatozoa incubated with FS, and relative mRNA expression associated with ODF2, ZPBP2, and AKAP4 were downregulated in sperm exposed to FS. Therefore, FS can alter normal sperm functions and thereby impair male fertility in animals and humans.